Anishinaabe Dreamcatcher

- Anishinaabe Dreamcatcher Book

- Native American Mythology

- The Culture And Language Of The Minnesota Ojibwe: An Introduction

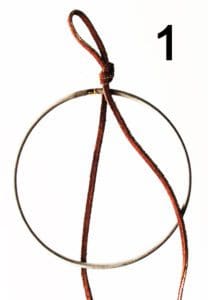

Dream Catchers Dream Catchers are a spiritual tool used to help assure good dreams to those that sleep under them. A dream catcher is usually placed over a place you would sleep where the morning light. Dreamcatcher; Aadizookaan. Traditional stories told by the Anishinaabeg are the basis for the oral legends. Known as the aadizookaanan ('traditional stories,' singular aadizookaan), they are told by the debaajimojig ('story-tellers', singular debaajimod) only in winter in order to preserve their transformative powers. Nanabozho stories. What Does the Dreamcatcher Tattoo Mean? Dreamcatchers are Native American in origin, and are believed to be protectors of people as they sleep, hence the name. Legend has it that a “Spider Woman” used to travel around the Anishinabe (Chippewa) tribe, weaving protective webs over newborn infants.

PrintShareCitationSuggest an Edit- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Horton, R.. 'Anishinaabemowin: Ojibwe Language'. The Canadian Encyclopedia, 18 December 2017, Historica Canada. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/anishinaabemowin-ojibwe-language. Accessed 07 February 2021.

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Horton, R., Anishinaabemowin: Ojibwe Language (2017). In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/anishinaabemowin-ojibwe-language

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Horton, R., 'Anishinaabemowin: Ojibwe Language'. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published November 14, 2017; Last Edited December 18, 2017. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/anishinaabemowin-ojibwe-language

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- Horton, R.. The Canadian Encyclopedia, s.v. 'Anishinaabemowin: Ojibwe Language', Last Edited December 18, 2017, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/anishinaabemowin-ojibwe-language

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission

and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Close| Published Online | December 18, 2017 |

| Last Edited | December 18, 2017 |

Terminology: Anishinaabe and Ojibwe

Though many may use the terms Anishinaabe and Ojibwe interchangeably, they can have different meanings. Anishinaabe can describe various Indigenous peoples in North America. It can also mean the language group shared by the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples. Ojibwe, on the other hand, refers to a specific Anishinaabe nation. Anishinaabeg is the plural form of Anishinaabe and consequently, refers to many Anishinaabe people.

Anishinaabemowin, the term often used to describe the language of the Ojibwe specifically, can also be used to describe a language spoken by other Indigenous peoples of North America. Ojibwemowin, sometimes used interchangeably with Anishinaabemowin, refers specifically to the language spoken by the Ojibwe people.

Algonquian Linguistic Family

Anishinaabemowin is part of the Central Algonquian language family, which is a group of closely-related Indigenous languages (such as Odawa, Potawatomi, Cree, Menominee, Sauk, Fox and Shawnee) with similar sounds, words and features.

The Central Algonquian language is part of the larger Algonquian language family, which spans from the Rocky Mountains (Blackfoot Confederacy territory) to the Eastern Seaboard (where Mi’kmaq is spoken).

Writing the Language

Anishinaabemowin began as an orally transmitted language.

Historically, there was a specialized form of symbol writing to communicate teachings sacred to the Ojibwe people. While Anishinaabeg continue to honour symbol writing, written forms of Anishinaabemowin using Roman orthography (i.e., the Latin alphabet, such as that used by the English language) is the primary form of written communication.

Christian priests and missionaries who traveled to Ojibwe territories were the first to write Anishinaabemowin using the Latin alphabet. (See alsoIndigenous Territory.) Slovenian Roman Catholic missionary Frederic Baraga actively learned Anishinaabemowin as a means of promoting the conversion of Indigenous people to Christianity. As a tool for fellow missionaries, Baraga authored the Dictionary of the Otchipwe Language in 1853. Otchipwe (a misnomer of Ojibwe) is a basis for the term Chippewa. The writing systems employed by missionaries can best be described as folk-phonetic style.

In 1840, Methodist clergyman and missionary James Evans created a system of syllabics following his travels among the Cree of Norway House. Using a system of glyph-symbols that represented combinations of consonants, vowels and final sounds, Evan’s system of syllabics spread widely among the Cree and Ojibwe peoples. Syllabics continue to be used in various capacities today.

Beginning in the mid-20th century, linguist Charles Fiero helped to develop the double-vowel system that is widely used today. Fiero’s system is considered easier to use than the folk-phonetic style, in which the spelling of words differs from person to person. An example of the difference between folk-phonetic style and Fiero’s system is as follows:

Action conveyed: “He/She is dreaming.”

Folk-phonetic style: Buh-waa-jih-gay.

Fiero’s system: Bawaajige.

Using Fiero’s double-vowel system, some vowel sounds may be long (aa, e, ii, oo) and some may be short (a, i, o), and the delivery of each sound can greatly alter the meaning. For example, zaaga’igan means “lake,” whereas the similarly-spelled zaga’igan means “nail.”

Speaking the Language

Traditional knowledge holders share that the language was originally created by Nanaboozhoo (sometimes spelled Nanabozo, also called Wenaboozhoo and Nanabush) after Gizhe Manidoo gave him life, lowered him to the Earth, and gave him the responsibility to name everything in existence. By means of Nanaboozhoo’s task, Anishinaabemowin was born and spoken into existence.

Elders often speak about the importance of Anishinaabemowin to Anishinaabe culture and society. In addition to routine communication, the language is essential in the officiating of Ojibwe ceremonies and the repatriation of sacred items as well as in providing a unique way of understanding the world. The survival of Anishinaabemowin is directly related to the survival of Anishinaabe identity and culture.

Cultural protocols and understandings are built into Anishinaabemowin communication. For instance, the word boozhoo (“hello”) not only acknowledges the original spirit of Nanaboozhoo and guides relationships based upon respect, but conveys the process of using the breath of life (“boo”) to express the feeling of life (“zhoo”). The word for old woman (mindimooyenh) describes one who holds everything together from the family to the nation. Bawaajige (“he/she is dreaming”) communicates travelling in the form of spiritual light when the body is at rest. Aaniin, which can be used as a greeting, conveys acknowledging the light within another person that is the same light within oneself.

Across linguistic regions, Anishinaabemowin speakers generally introduce themselves to someone new using a specific protocol. Following a greeting, the speaker mentions their spirit name in the Anishinaabe language. They also acknowledge their home or territory, as well as acknowledging their clan. This is a spiritual identification, but it also helps others to understand differences in protocol that a person may have learned over the years.

Notable Features

Verbs

Anishinaabe Dreamcatcher Book

Anishinaabemowin is dominated by verbs. Concepts of life, process and action are woven into the fabric of the language. General categories of verbs used to express a thought in Anishinaabemowin include:

- Verb animate intransitive (where a living subject is doing something/being a certain way)

- Verb animate intransitive + object (where a living subject is doing something/being a certain way to a being or thing that remains vague and general)

- Verb inanimate intransitive (where a non-living subject is doing something/being a certain way)

- Verb transitive inanimate (where a subject is doing something/being a certain way to a non-living thing)

- Verb transitive animates (where a subject is doing something/being a certain way to a living being)

Genders

There are also two “genders” of nouns: animate (living beings with agency) and inanimate (non-living things). Animate and inanimate are linguistic classifications. Depending on which style of noun is used, the verb used to compound the noun into a statement may be animate (verb animate intransitive and verb transitive animate) or inanimate (verb inanimate intransitive or verb transitive inanimate).

Inini — “man” (animate noun)

Bimibatoo — “He/she is running by.” (verb animate intransitive)

Bimibatoo inini. (“The man is running by.”)

Adoopowinaak — “table” (inanimate noun)

Michaa — “It is big.” (verb inanimate intransitive)

Michaa adoopowinaak. (“The table is big.”)

Consonants and Glottal-stop

Not all consonant sounds found in the English language are also found in Anishinaabemowin, but Anishinaabemowin does contain new consonant sounds such as ch, sh, zh, and a glottal-stop (represented by an apostrophe in the written form). A glottal-stop is a short pause, similar to the English interjectional expression “uh-oh.”

Referring to Third-persons

One of the more unique features of Anishinaabemowin is the system of obviation, where a clause can contain references to more than one third-person. The main third-person (he/she, also known as the proximate) is the main focus of a statement, meaning that he or she is central to the story or speaker. If present, the other third-person is called obviative, meaning that he or she is secondary and in-relation to the first person. A suffix on the obviative noun (where it is pluralized and the “g” changed to an “n”) distinguishes this person as the obviate, as seen in the following sentence: “John makwan odoodeman,” meaning “John’s clan is the Bear.”

Current State of the Language

Anishinaabemowin is a considered an endangered language. Assimilationist policies and programs, such as the residential school system in Canada (and the boarding school system in the United States), have led to the decline of language use.

However, there are efforts to revitalize the language. Immersion programs allow students to speak the language regularly. Ojibwe language and teacher education programs (such as those at Lakehead University, Algoma University, University of Manitoba and others) are also central to revitalization efforts, as are publications and print resources (such as the bilingual Oshkaabewis Native Journal), community and workplace language tables, and technology resources (such as video tutorials, webinars and mobile phone apps).

Research has demonstrated that Indigenous peoples’ acquisition of traditional languages correlates to increased self-esteem and community well-being, among many other positive gains. In 2017, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau proposed an Indigenous Languages Act to assist with the protection and revitalization of Indigenous languages, such as Anishinaabemowin.

Kevin Callahan

Spelling: Ojibway, Ojibwa, or Ojibwe?

According to Professor Dennis Jones who teaches the Ojibwe language at the University of Minnesota, either Ojibwe or Ojibwe are actually correct spellings, but some people feel Ojibwe should be the preferred standardized spelling. I have chosen to use the Ojibwe spelling only because that is the way I originally learned it. If I had it to do over again I would probably use Ojibwe.

The Ojibwe Totemic or Clan System

According to Eddy Benton-Banai (1988) the Ojibwe clan system was a system of government and a division of roles and labor. William Warren, listed 21 totems (both by their Ojibwe name and in English), noting that, according to oral tradition, in the beginning there were only five. Originally the totem descended through the male line and individuals were not to marry within their own clan. According to Warren, the principle totems were the “crane, catfish, bear, marten, wolf, and loon” (Warren 1885:45). Warren indicated the English name for the more extensive list of 21 totems to be as follows: Crane, Catfish, Loon, Bear, Marten, Rein Deer, Wolf, Merman, Pike, Lynx, Eagle, Rattlesnake, Moose, Black Duck or Cormorant, Goose, Sucker, Sturgeon, White Fish, Beaver, Gull, and Hawk Warren 1885:44-45).

Ojibwe Spirituality

In general terms, Ojibwe spirituality centers around certain customs and beliefs, concepts, events, and objects. These include the sweatlodge, pipe, drums, singing, the naming ceremony, prayer, vision questing and guardian spirits, the Pow Wow, the medicine man or woman (shamans), medicine bags, dream articles and traditional stories regarding the Great Spirit, Creation, Original Man, The Flood, etc. Ritual and spiritual objects include sage,sweetgrass,tobacco, and cedar. Dogs were akin to the sacrifical lambs of early Christianity. There are 4 seasons and 4 grandfathers (or 4 powers of the universe) sit at the four cardinal directions of North, South, East, and West. The symbolic “four colors of man” are red,yellow,black, and white. Listen to Frances Densmore’s Audio Cylinder Recordings (RealAudio Player – loads fast) or watch a QuickTime Movie about the Ojibwe (5 mgs).

Important Terms and Concepts related to the Ojibwe Creation Story:

Boo-zhoo’ means “hello” (and indirectly makes reference to the idea that Ojibwe are related to Original Man or Anishinabe also known later as Way-na-boo’zhoo or Naniboujou, etc). Mi-gwetch’ means “thank you” and Mishomis means “Grandfather.” Since everything in the world was created before Original Man many things are referred to as “Grandfather.”

Madeline Island in the Apostle Islands in Lk. Superior is significant because the Ojibwe believe their ancestors migrated there from the east coast of No. America and it was their final stopping place after 500 years of migration following the dream of the prophet of the First Fire to move or be destroyed. Teachings about Ojibwe history are passed down orally. Birch bark scrolls were used to write down things using pictographic writing (a mneumonic or memory device using pictures and symbols rather than a phonetic writing system).

Ah-ki’ (the Earth) is a woman and had a family. The Sky is called Father. Nee-ba-gee’sis (the Moon) is called Grandmother. Gee’sis (the Sun) is Grandfather. Gi’-tchie Man-i-to’ (Creator or Great Mystery) is the Creator. The four directions – North, South, East, and West are very important. The physical and spirtual duality is represented in the four directions. It is thought that medicinal plants when physically picked will not work unless there has been the proper spiritual behavior (such as offering tobacco, etc.).

“Gitchie Manito…took four parts of Mother Earth (earth, wind, fire, and water) and blew into them using a Sacred Shell [the Megis or Cowrie Shell]. From the union of the Four Elements and his breath, man was created” (Benton-Benai 1988:2-3).

According to Benton (1988:3) Anishinaabe (the older term for Ojibwe) means ani (from whence), nishina (lowered) abe (the male of the species). Others translate it as first male or first man or original man.

Original Man was lowered to the Earth according to this creation myth and all No. American tribes come from him.

The Ojibwe are a tribe because of the way they speak (Algonquian language).

Traditional people call North America “turtle island” because it is shaped like a turtle (Florida is one hind leg, Baja California is another, Mexico is the tail). In the Ojibwe Story of the Great Flood the turtle offered its back to Waynaboozhoo to bear the weight of the new earth. The new earth was formed from a piece of earth recovered by muskrat from the bottom of the water which covered the world.Cf. Noah & The Flood The expression “there are many roads to the High Place” means Nat. Americans should support and respect each other’s traditions and one tribe’s beliefs can shed light on the others. According to the Ojibwe creation story the Original Man’s first responsibility after he was placed on Earth was to follow the Creator’s instructions and walk the Earth and name all of the animals, plants, hills, and valleys. He also named the parts of the body.Cf. Genesis Many English words are derived from the Ojibwe language such as: Mississippi “Miziziibi”(large water), moccasin “makizin,” moose “mooz,” pecan “bagaan” (nut), toboggan “zhooshkodaabaan,” Milwaukee “mino-aki,” etc.. The rivers that run underground are the veins of Mother Earth and water is her blood, purifying her and bringing her food. Mother Earth implies reproduction and fertility and life.

The Creator, Gitchie Manido, sent the wolf to keep Way-na-boo-zhoo, Original Man, company while walking around creation. After they completed that task he ordered Original Man and Wolf to go different ways.

The wolf and man (the Ojibwe) are thought to be similar because both walked creation, mate for life, have a Clan system and a tribe, have had their land taken from them, have been hunted for their hair, have been pushed close to destruction and are recovering.

Dogs should never be at sacred ceremonies because dogs are the Ojibwe’s brothers as much as the wolf was a brother to Original Man. Because the Creator separated the paths of the wolf and Original Man, the dog who is a relative of the wolf should be separate from contemporary people and should be kept separate from sacred ceremonies and where ceremonial objects are stored or it could endanger people’s lives.

The Naming Ceremony

The Naming Ceremony, which remembers the sacrifices of Original Man in naming everything, requires that a medicine person be asked by the father and mother to seek a name for their child. The seeking can be done through fasting, meditation, prayer or dreaming and the spirits give the name. At a gathering the medicine person burns tobacco as an offering and pronounces the new name to each of the 4 Directions and everyone present repeats the name when it is called out. The Spirit World then accepts and can recognize the face of the child as a living thing for the first time. The Spirit World and ancestors then guard the child and prepare a place for him or her when their life ends. At the naming ceremony the parents ask for four men and four women to be sponsors for the child. The sponsors publicly vow to support and guide the child. This naming ceremony is thought to have been started by Original Man.

The Ojibwe Migration Story

According to oral tradition the Ojibwes and other Algonquin speakers were originally settled up and down the East Coast. Those who do not share this traditional view think it is more likely the Ojibwe lived next to Hudson’s Bay and moved southward. Traditional Ojibwe spiritual leaders are creationists and do not believe in the Bering Strait hypothesis for the peopling of North America nor the evolution of human beings in a Darwinian sense. Traditional oral history indicates that the early Ojibwe planted corn and used canoes, overland trails, and sled dogs and sleds in winter. According to they oral traditions the Ojibwe Daybreak people (Wa-bun-u-keeg’) vowed to stay in the east and may be the people the French referred to as the Abnaki. The prophet of the 1st Fire told the people to move or be destroyed. Most of the Daybreak people were later destroyed when the whites came. The Mide (shamans) remembered the prophet of the First Fire speaking of a turtle shaped island that would be the first of seven stopping places during the Ojibwe migration. There are two sites that fit the description. The first is at the mouth of the St. Francis River and the other is an island near Montreal. The 6 Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy were major adversaries during the migration. The seven major stopping places of the great migration were 1) turtle-shaped island (Montreal?) 2) Niagara Falls 3) the Detroit River 4) Manitoulin Island in Lk. Huron 5) Sault Ste. Marie 6) Spirit Island in Duluth and Madeline Island in the Apostle Islands of Lk. Superior. The Megis Shell rose up out of the water or sand at each locale and they knew when to stop when they found a turtle-shaped island (Madeline Island) and “the food that grows on water” (wild rice).

The Ojibwe have a 3 Fire confederacy composed of the Potawatomi (the fire people; keepers of the Sacred Fire), the Ottawa (the trader people), and the Ojibwe (the faith keepers; keepers of the sacred scrolls and the Waterdrum of the Midewiwin (the organized shamanic society for healers). All of the Anishinabe people are the nation of the Three Fires. Benton-Banai thinks the people were mistakenly referred to as the Chippewa. Densmore said that: “The meaning of the word Ojibwe has been the subject of much discussion. The derivation of the word from a root meaning “to pucker” has been conjectured. Many attribute this derivation to a type of mocassin formerly used by this tribe, which had a puckered seam extending up the front instead of having a tongue-shaped piece, as in present usage” (Densmore 1979:5-6). The Three Fires nation was attacked along the migration by the Sauks and Foxes and never fought the whites. They fought battles with the Dakota when they got to the Midwest. Benton-Banai thinks the migration started around 900 AD and took about 500 years to complete (1988:102). He believes the Sacred Fire was kept alive that long and the dream of the original 7 prophets was carried by many generations.

Ojibwe Dream Articles: Physical Objects Representing or Interpreting Dreams and Visions

According to Anthropologist, Frances Densmore (1867-1957), physical objects such as stone pipes, a horned cap, woven yard cords, paintings and drawings on cloth, blankets, headgear, miniature objects given to children, and woven beadwork such as headbands or neckbands worn tightly around the neck, frequently represented the subject of important dreams and visions, and represented them either by imitation or interpretion (Densmore 1979:78-86).

She wrote that: “It was the belief of the Chippewa that by possessing some representation of a dream subject one could at any time secure its protection, guidance, and assistance. There seems to be inherent in the mind of the Indian a belief that the essence of an individual or of a ‘spirit’ dwells in its picture or other representation” (Densmore 1979:79).

Native American Mythology

“[F]asting, isolation, and meditation” were the main methods to obtain a dream (Id.). The dream representation could be either made into an object or outlined as a picture and could be “either an exact representation or an article or outline more or less remotely suggesting a peculiarity of the dream. The representation published the subject of a man’s dream but seldom indicated the nature of the dream” (Densmore 1979:80).

Stone was favored for its enduring properties and on older man told Densmore: “A picture can be destroyed, but stone endures, so it is good that a man have the subject of his dream carved in a stone pipe that can be buried with him. Many of his possessions are left to his friends, but the sign of the dream should not be taken from him” (Id.).

Protective charms could be either direct representations or symbolic representations of dreams. The possession of a woven yard cord with the color white woven into it, when tied around the waist of a woman who had dreamed of a safe trip on a large lake, was believed to provide protection to her when traveling (Densmore 1979:80-81,111). As Densmore points out: “A personal fetish was usually a crude representation of an object seen in a dream, either by the wearer or by someone who transferred it to him, together with the powers or benefits accruing from the dream” (Densmore 1979:111). A husband who dreamed of the bear when he was young, could strengthen his very ill wife by spreading a cloth with the image of a bear over her and later hanging it by her head as she was getting stronger. A man who had dreamed of a rainbow, thunder bird, lightning, and the earth (indicated by a circle) painted it on a blanket and wore it around his back for everyone to see and fastened it across his chest (Id. at 82). A man who dreamed of an unusually shaped knife made one and carried it in battle. A woman who saw a winged figure in a youthful dream carried a representation of the figure made of black cloth and bordered with white beads, “believing that she has secured supernatural guidance from its presence. . . . When in doubt she has ‘always seemed to have a mysterious guidance’ that has led her to a successful solution of her difficulties” (Id. at 86). Beadwork incorporating dream representations were common in headbands and neckbands (Id.).

After recounting various physical objects Densmore notes: “From the foregoing instances it is evident that the subject of a man’s dream was clear to all intelligent observers, but its significance was a secret that he might hide forever if he so desired” (Id. at 83). One man related that he was able to increase his strength by wearing a horned cap similar to a horned animal seen in a dream. He believed “in the power of a dream article, as well as the making of an article in accordance with a dream” (Densmore 1979:85).

Dream articles were also given to children by their medicine man (or woman) namer. Densmore wrote that: “Miniature representations of dream objects were frequently hung on a child’s cradle board, the child deriving a benefit connected with the nature of the dream. Such articles were usually given the child by the person who named it, and were in accordance with the namer’s dream” (Densmore 1979:113). In Chippewa Customs is an illustration of an upside down lunate that was given to a small child to be worn around the neck.(Figure 8, Densmore 1979:55). The shaman who named the child (after dreaming for the name) gave the “token” to the small child “‘in order that the child might care for him’ This consisted of something that might attract the fancy of the child and was usually worn around its neck by a cord” (Id.). It is not clear from Densmore’s description but the upside down lunate may be a dream article related to the namer’s dream that gives him or her power, or it may be a representaion of the child’s dream name. Densmore gives two clear examples of medicine man namers who gave dream articles to children they named and one example of a similar practice where a namer gave a dream article to an adult. The man, mentioned above, who dreamed of a peculiarly shaped knife, “always gave a miniature of this knife to they boys that he named. Another man always gave a little bow and arrow to his namesakes. A dream article given to an adult by a namer is noted in a subsequent paragraph” (the woven yard cord with white cord woven into it)(Id.). The power to name children is derived from a shaman’s dream (Id. at 56). In the case of the adult woman who was named by another woman: “The namer. . . related [the namer’s] dream, announced the name, and presented an article made to resemble the subject of the dream” (Id. at 58).

As Densmore notes: “It was considered desirable that the representation should be put in as enduring a form as possible,” and as one old man told her, “stone endures” (Densmore 1979:80).

Ojibwe Rock Art: Physical Artifacts Representing or Interpreting Dreams and Visions

The physical objects of Ojibwe culture that perhaps most permanently recorded and represented their dreams, visions, representations of dream names, and mythical figures was the rock art. As Vastokas and Vastoukas (1973:44-45) have pointed out, based on their analysis of Henry R. Schoolcraft’s descriptions, (1851-1857), there were actually two kinds of pictographic images that the Ojibwa would render in stone. Schoolcraft was himself part Ojibwa and was the Ojibwa Indian agent at Sault St. Marie, Michigan from 1822 to 1841. The Ojibwa pictography termed “Kekeewin” could be “incised upon birch bark scrolls as memory aids in the singing of Mide songs, as heraldic devices identifying clan affiliation or representing personal totems carved on the trunks of trees, as images placed on gravemarkers, and as glyphs pecked out or painted on rocks or boulders” (Vastoukas and Vastoukas 1973:43). These were generally known and understood. “Kekeenowin” on the other hand “are shamanistic renderings of visionary experiences” and were more symbolic, secret, and sacred rather than secular. “Muzzinabikon” or rock writing, most often recorded “the visionary experiences” of Ojibwa shamans (Vastoukas and Vastoukas 1973:44).

The Algonquian Language Family

The Ojibwe (Ojibwa,Ojibwe) language is spoken in the southern portions of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Ontario, and northern areas of MN, MI and WI. It is part of a larger language group called the Algonquian Language Family. The four main parts of the Ojibwe people are 1) The Northern Ojibwe in central Canada, 2) the SE Ojibwe in Ontario, northern Ohio, etc., 3) The Chippewa in MN, WI, and MI, 4) the Plains Ojibwe in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and ND (see Ojibwe Maps).

The Algonquian Language Family originally extended NE of a line from North Carolina to the Great Lakes excluding upstate NY and southern Ontario, and the Ohio Valley. Now it extends from the Maritime Provinces in Canada to Alberta, including Michigan and the western Great Lakes area, and scattered settlements in MT,KS,IA,OK and northern Mexico. The Algonquian languages include Micmac, Maliseet-Passamoquoddy, Etchemin, Penobscot, Caniba, Aroosagunticook, Sokoki-Pequaket, Western Abnaki, Pennacook, Pentucket, Loup A, Loup B, Massachusett, Wampanoag, Cowesit, Narragansett, Mohegan-Pequot, Montauk-Shinnecock,Quiripi,Unquachog, Mahican, Delaware languages, Munsee, Unami, Unalachtigo, Unami, Virginia Languages, Nanticoke-Conoy, Powhatan, Chickahominy-Appomattox,Pamunkey-Mattapony, Nansemond, Carolina languages, Chowan, Pamlico, Cree Languages, Eastern Cree, Naskapi, Montagnais, East Cree, Western Cree Atikamek, Moose Cree, East Swampy Cree, West Swampy Cree, Woods Cree, Plains Cree, Ojibwe languages, Northern Ojibwa, Algonquin, Severn Ojibwe, Eastern Ojibwe, Ottawa, Central Ojibwe, Lac Seul Ojibwe, Southwestrn Ojibwe, Saulteax, Potawatomi, Menomini, Fox, Sauk, Kickapoo, Mascouten, Miami-Illinois, Shawnee, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Atsina, Blackfoot, Blood, Piegan, Ritwan, Wiyot, Yurok.

The Culture And Language Of The Minnesota Ojibwe: An Introduction

Sources:

– Chippewa Customs by Frances Densmore 1979 Minn. Hist. Soc. Press (Reprint of the 1929 ed. published by the U.S. Govt. Print. Off., Wash., which was issued as Bull. 86 of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of Amer. Ethnology). Frances Densmore (1867-1957) was an excellent anthropologist who among other things recorded Nat. American songs. This book can be bought at the MN Hist. Center in St. Paul, MN or from the U of M Bookstore on the east bank.

– The Mishomis Book, The Voice of the Ojibwe by Eddy Benton-Banai 1988 Indian Country Communications, Inc., Hayward, WI. This book is from the Red School House and is “based on the oral traditions of the Ojibwe people.” This book can be bought from the U of M bookstore.

– AMIN 3026 Ojibwe Culture and History, Dennis Jones, Instructor, U of MN Fall 1998. Email: jones112@maroon.tc.umn.edu The Course Packet for this course is available from Paradigm Resources in the Dinkydome in Dinkytown, Mpls., MN.

– Sacred Art of the Algonkians, A Study of the Peterborough Petroglyphs Vastoukas, Joan M. and Romas K. Vastoukas 1973. Mansard Press: Peterborough. Copies of this book may also still be available by writing Joan Vastoukas.